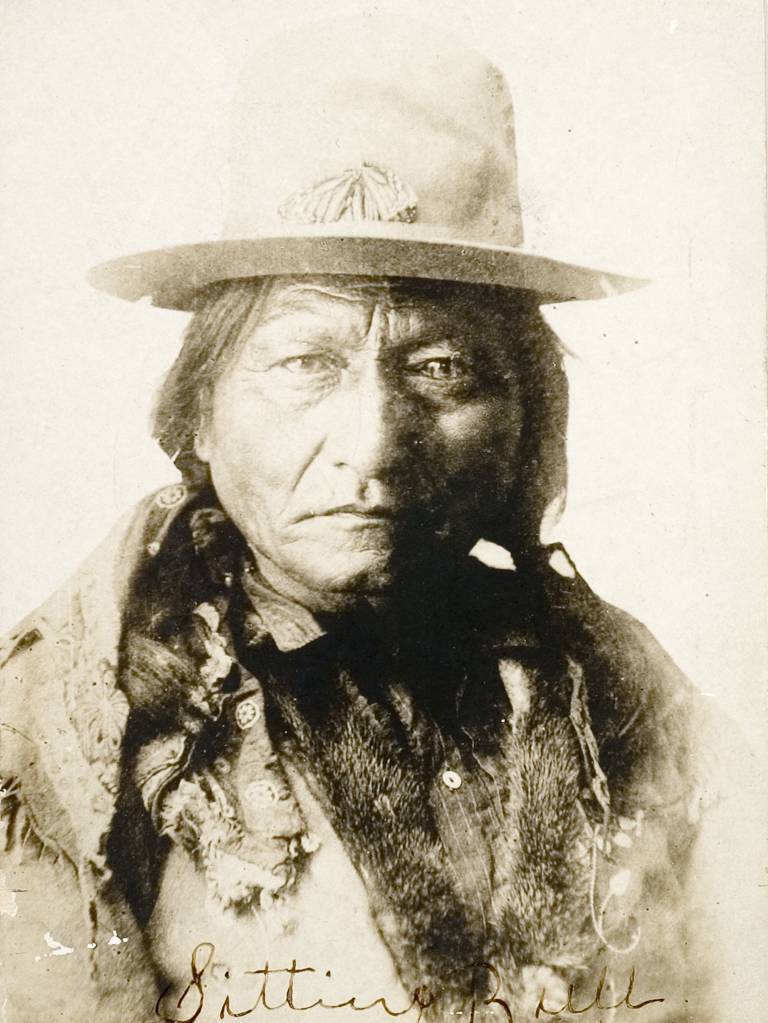

Hunkpapa Lakota tribal leader and oracle Sitting Bull (Tatanka-Iyotanka) believed that dreams and waking visions could foretell the future and it is claimed that they helped him win a major military victory against more technologically advanced US forces at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Sitting Bull’s and other Native American dreaming experiences beg the question – have we lost sacred knowledge about the power of our dreams? And can we use our dreams today to fight injustice in the world? This article will take a look at Native American dreaming culture, history and visions.

The Diversity of Tribes

The importance of dreaming is replete throughout Native American cultures. However, it is quite common to see popular culture in the West, and especially new age spiritual teachers, portray the Native American world as a homogenous entity, whereas the reality is of course that these cultures are much more heterogenous, rich and wonderful than many first envisage. When considering various rituals and practises across Native North America, it is crucial to think about the diversity of such groups – visions and dreams may have different types of rituals, practises and meanings associated with them depending on the tribe. Indeed, across tribes, there are variations in beliefs about where dreams come from, what they are, their purpose, and how to best incubate them. Such differences represent the vast plethora of cultural variation that helps shape, define and limit, the dreams of individuals and groups across the region.

When the tyrant Christopher Columbus arrived to the Bahamas and beyond, America and Canada had over 300 distinct cultures and spoke over 200 languages (Nabokov 1991: 4). These numbers dropped dramatically due to diseases such as smallpox, influenza and measles, as well as warfare, genocide and terrorism; with estimates suggesting that in the Americas as a whole, 10% of the total world population was extinguished. There are now 574 tribes Federally registered today in the United States, or when including the Continent what is known to a lot of Native Americans as Turtle Island. There are many hundreds of state registered and non-registered groups that exist alongside these ‘official’ estimates as well. A great number of these tribes share a cultural and historical heritage that is passed down between clans. Such clans have also been characterised by their shared languages and the geographical spaces which they inhabit, such as the Plains, Arctic and South West regions. There were often changing treaties and unions between tribes like the Iroquois of the North East, whilst other tribes constantly fought one another – relations between groups were not always rosy.

The Soul, and the Dreaming and Waking States

Yet, alongside these differences, the importance of dreams and visions for gaining power in groups, for self-development and enhancing cultural knowledge, were loosely shared across many tribes. To a lot of these groupings, the soul exists and can travel to other realms in our dreams and in trance-like states. It is thought too by some such as the Zuni and Hopi tribes that it is our breath that leaves the body to travel when we dream, and that it can travel to upper and lower dimensions – to the realms of the gods and the dead and to see our ancestors. Dream spirits are also thought to pass on prophetic dreams that are viewed as being quite different and set apart from other personal dreams which they received. It should come as no surprise then that belief in reincarnation is also common to many groups. Some dreamers see their past lives in their sleeping or waking-state visions and other dreams are seen as being a continuation from before we are even born!

Most tribes also included some form of animist and supernatural belief structure about the world around them that entwined itself with the dream world. Healing manitos were powerful spirit guides that could take the form of animals who could visit dreams. These spirit animals are often seen during vision quests. The manitos can help dreamers mend a part of their personal lives and develop parts of their psyche or soul too. In some tribes the soul is perceived to act in a dualistic way, with one part acting as a site for emotions and human consciousness in the heart space, and another which can leave the body and interact with these manitos in dreams or the waking world. Therefore, it is evident in such societies that children could be taught and encouraged from a very young age to lucid dream, interact with dream characters and animal spirit guides (sometimes seen as parts of their own psyche), and develop a positive relationship with dreams. In order to gain such lucid dreams and additionally meet guides in that space, one would need to ‘set up’ their dreaming and to have a second dream by training yourself to fall asleep in the first dream.

Dreams can also be seen in some tribes as a composite of every day lived life. Tribes such as the Blackfoot and Hopi saw dreams as a way to solve every day problems in the waking world, like passing on instructions to do with hunting and healing. A great deal of modern research has confirmed the power of such dreams for helping to improve brain and muscle memory. Much wisdom and special knowledge is gained through dreaming. Tribes such as the Mojave, Maricopa and Klamath sing songs that are said to have been received from their dreams which they believe came from the very beginning of the universe. Such songs are also used to heal the sick during ceremonies, stave off illness, preserve the languages of tribes, and generally keep them alive. Tribes like the Crow used dreams to glean painting methods from them too.

The dreaming and the waking worlds are oftentimes seen as being very much intertwined, and less distinction is usually made between the two in Native American thought. In some cases, rather than dreams being seen as a reflection of the waking world, the waking world is also seen to be a mirror of our dreams. This is evidenced in how a few tribes like the Zuni do not see a dream being complete until the action dreamt, such as hunting, is actually performed in waking life. In other instances, tribes see dreams as being more ‘real’ than the waking world. The Hopi believe that dreams are real experiences and so it is important to also confess the negative aspects of dreams to others in their community. The Alaskan Eskimos believed that only good dreams should be shared with others, whilst bad ones should be kept to themselves. Other various tribes felt that such dreams should indeed be shared, or in some cases even that people should be whipped or that rituals or initiations into medicine societies be carried out if such negative dreams take place. These offerings would be made for a multitude of reasons and take many forms. The Crow would make offerings if they dreamt that someone they knew would get ill; they would then cut off their hair and throw it into water along with other items. There is certainly a lot of variability across tribal dreaming culture.

Vision Quests, Myths and Ceremony

Ceremonies were used to receive dreams and visions in many tribes. These were called vision quests. Visions were often received away from others, usually in isolation or upon a high place such as a hill. Men would carry out dance routines, they would fast, pray, and conduct other rituals to help cleanse themselves before they hoped to receive these visions in trance-like states or in their dreams. More formal vision quests were taken part in by adolescents in order to meet their spirit guides and go on heroic journeys, receive visions and dreams. They hoped to gain life guidance, healing, protection and spiritual insight through using these tools. Girls also took part in ceremonies but did not often venture out alone to the mountains and hilltops. They would similarly fast and wait to receive a spirit who would take them to another realm and pass them the gift of longevity, psychic powers such as clairvoyance, and knowledge of herbal medicine. The record of female journeys is unfortunately much less well documented from verbal history than their male counterparts, although there have been and are many powerful female Shamans.

The story of the coming of the White Buffalo-Maiden outlines how many of the 7 Sacred Ceremonies that the Lakota people practise today in order to gain visions and other benefits came into existence. These benefits include; spiritual insight, guidance, healing and special dreams and visions. In the story, the female prophet, the White Buffalo-Maiden, was said to have acted as a messenger from Wachan Tanka, otherwise known as the Great Spirit, after she arrived in a mysterious mist and later left and transformed into a white buffalo calf and passed on the tribe’s 7 Sacred Ceremonies and a Sacred Smoking Pipe. One of the 7 Sacred Ceremonies included the Sun Dance. This involves enduring the pain of piercing the skin in a symbolic act that is said to demonstrate the importance of self-sacrifice and the giving of yourself for the benefit of others. These practises were outlawed by the US government and religious groups – who thought them to be barbaric.

The Destruction of Cultures and its Foretelling

The perceived abilities of individuals and groups to see the future through various means were very often equated with the work of the devil by white ‘settlers’. Nonetheless, the belief in Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit, or Great Mystery, was often used by Christians in an attempt to convert Native Americans to their monotheistic religion; noting perceived similarities between them. Nonetheless, dependant on the tribe, sometimes multiple deities existed. These settlers helped destroy many aspects of indigenous culture and some Christian missionaries attempted to ban and discourage ceremonies and rituals altogether.

Indigenous people were very often depicted as savages from the earliest stages in American history and this contributed to damaging the many cultures that they fostered, causing tribes to form secret societies and temporarily seek refuge in countries like Canada. These early depictions of indigenous people can even be seen in the Declaration of Independence, a caricature later fuelled by ideas such as Manifest Destiny in 19th Century. The Declaration of Independence stated in relation to English King George III:

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian savages, whose known rule of warfare, is undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

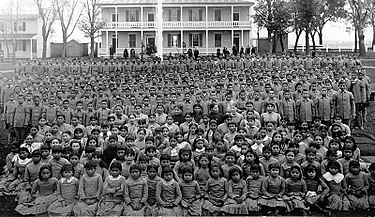

Huge levels of violence, terrorism and genocide were carried out on Native Americans in attempts to strike fear into tribes. So-called ‘Indian hunts’ led to the murder of tens of thousands of men, women and children and many were put into forced servitude. Later, policies to ideologically instil ‘white values’ were enforced, such as creating boarding schools through the Bureau of Indian Affairs to indoctrinate individuals toward industrialist and Christian ideals – many children were forcibly removed from communities and told falsely that their parents had been killed, their hair was often cut short, and oftentimes they were not allowed to speak in their native tongues or learn about their cultures in these schools. It was cultural genocide in the guise of ‘assimilation’ and existed up until as late as 1973.

Before white Europeans arrived to the continent en mass, many Native Americans prophesised that strange white men would arrive to their lands. These prophecies were often recorded in the diaries and logs of European travellers to the region. In one salient Sauk tribal story, the grandfather of Black Hawk had prophesised meeting white men who would act as a father in 4 years time, spurring tribesman in the waking world to travel ‘Eastward to a certain spot,’ where they actually met French soldiers and formed an alliance (Spence 1988: 19). The leader of the foreign soldiers was the son of the French King, and he claimed to have also had similar dreams over 4 years in which he’d met a tribe who had never seen white men before, and who would be like his children and see him as a father too.

How dreams and visions helped the fight against imperialism

The legend of Sitting Bull

Amidst this mass genocide and rampant disease, strong leaders arose. Born in 1830, Sitting Bull was first known as Jumping Badger and grew up amongst the Hunkpapa tribe, a group that makes up one of the 7 Lakota tribes in the Dakotas. Otherwise known as the Sioux, they were collectively known as the Seven Council Fires and were also split based on the spoken Sioux dialects of Lakota, Dakota and Nakota, and geographically divided by land area; Lakota, West Dakota and East Dakota. Sitting Bull was known as a Wichasa Wakan, a holy man who could receive insights about the future. Dream societies brought together men who shared similar visions. Sitting Bull was a member of several and it was through Wakan Tanka that many of his visions were received.

At the age of 14, Jumping Badger gained his most well-known name, Sitting Bull, after killing a Crow tribesman during a raiding party. Sitting Bull gained further fame and notoriety after sitting in front of US infantry who were helping to protect the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Sitting Bull walked to an area in full sight of the US Army and sat down with several other tribesman to show their disdain for troops for trespassing onto their lands to construct railroads. They began smoking their pipes as troops opened fire on them. The Native American men then walked off, but not before gently and carefully cleaning their smoking pipes as bullets whizzed past their heads.

Sitting Bull used particular incubation techniques in order to gain prophetic dreams and visions. Before one of his most famous visions was received before the Battle of Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull carried out the Sun Dance along with 5000 Lakota warriors. Immediately prior to this he made offerings by going without food and water for 2 days and cutting flesh from his arms. After dancing for hours he put himself into a trance. He then had a vision where he saw white troops and their hats falling from the sky into their camp ‘like grasshoppers.’ He interpreted this to mean he would gain victory against the US government forces.

Colonel George Custer’s US forces had previously violated the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, or Sioux Treaty. The Treaty setup reservations in Dakota, and offered protection if tribes were attacked, stating that the Black Hills would not be settled by whites. After Custer’s previous illegal expedition in 1874 a gold rush began and the treaty was largely disregarded. On the 25th of June, 1876, an alliance between the confederated Lakota Tribes and the Northern Cheyenne defeated the American forces of Colonel George Custer, after they stumbled across a huge gathering of between 12,000 and 15,000 Plains Indian warriors along the Little Bighorn River, Montana. Custer’s 7th Cavalry were surrounded, and 225 of them were killed, including Custer by men led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and Two Moons.

Native Americans were later forced to report to tribal agencies and live in squalid and often exploitative conditions on the reservations, causing Sitting Bull to flee to Canada in 1887. After returning, Sitting Bull even began performing for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. In 1889/90, the Lakota tribe began conducting the Ghost Dance, which the prophet Wovoka, of the Paiute tribe had reintroduced. The Ghost Dance attempted to communicate with old ancestors with the aim to bring back life before the settlers arrived. Its impact was seen to be a huge threat to US central power. In 1890 Sitting Bull was shot dead as a result of fears he’d join the Ghost Dance movement were acted upon and tribal police were sent to arrest him. An Oracle had passed on to the afterlife.

Crazy Horse Sees the Future

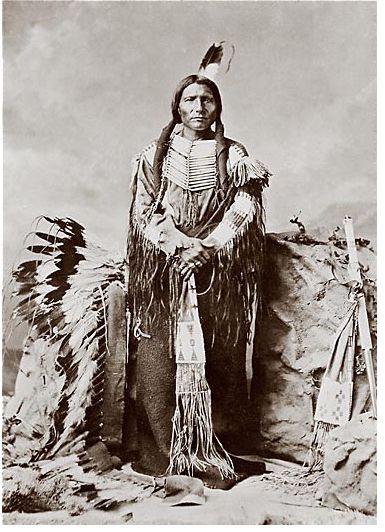

Another warrior that led the victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn was Crazy Horse, from the Oglala Tribe. Born in 1841, he was the son of a Shaman and the last Lakota leader to surrender to the United States government. Crazy Horse was born to a family that could see the future, but most interestingly, he did not always follow the traditions and rituals of the Sioux. After US military officers, who often used the Holy Road through Lakota lands, killed an elderly man in front of him, Crazy Horse prayed for a vision from Wakan Tanka. After 3 days he saw a dream where his own pony changed the colour of its fur above him. He then saw a warrior who appeared invisible to enemy bullets and arrows, but later saw his people holding him back. Indeed, in the waking world Crazy Horse did lead a raid against a group of Arapaho tribesmen and his dream gave him the strength to ride through the incoming arrows and bullets. Crazy Horse’s first vision proved correct again as he was eventually handed into government authorities by his own people after Red Cloud, another Oglala Lakota leader, pursued him and went on to hold Crazy Horse captive.

After an unspeakable massacre at Black Kettles Band, Crazy Horse asked for another vision. When he received one, he foresaw a great victory where he viewed an eagle soaring high above the tree-line; a damaged feather fell from the sky – on December 21st 1866 Crazy Horse’s band inflicted the largest military defeat on US forces on the Plains at this time and destroyed the enemy forts upon their land in what was known as The Battle of the Hundred in the Hands. This name was given because of an oracle who rode on his donkey between the camped Native Americans and the US forces; each time he came back to the camp the hermaphrodite prophet had visions of his hands overflowing with hundreds of US soldiers. This was taken as a good omen before battle.

To conclude, whilst many cultures were wiped out and diluted by European settlers, the dreams and visions of legendary leaders such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse show that despite the destruction, hope remains in fights against injustices in this world. The dreaming practises of many Native Americans were varied and highly influenced by the external environment around them. Culture shapes and limits our dreams as well as expands them beyond the limitations we impose on our lives. Yet, it remains clear that by looking at the varied beliefs of Native American cultures, our culture in the West severely limits our understanding of both the waking and sleeping realms as it is often forgotten that: ‘Sometimes dreams are wiser than waking.’ (Black Elk in Nabokov 1991: 17).

Sources:

Allan, T. (2002) Prophecies: 4,000 Years of Prophets, Visionaries and Predictions. London: Duncan Baird Publishers.

America’s Great Indian Nations, Retrieved from (4746) America’s Great Indian Nations – Full Length Documentary – YouTube

Bahr, D. (1994) Native American Dream Songs, Myth, Memory, and Improvisation. Journal de la Société des Américanistes , Vol. 80 (1994): 73-93.

Drury, B. and Clavin, T (2013) The Heart of Everything that Is: The Untold Story of Red Cloud, an American Legend. New York: Simon and Schulster.

Hercules, R. (2002) Great Indian Leaders. Questar Entertainment: Chicago

High-Tower, L. (2003) The Native American World. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: New Jersey.

History Channel Editors (2018) Crazy Horse. Retrieved from Crazy Horse – HISTORY

History Channel (2020) 10 Things You May Not Know About Sitting Bull Retrieved from https://www.history.com/news/10-things-you-may-not-know-about-sitting-bull

History Channel (2020) Native American Cultures – Facts, Regions, and Tribes. Retrieved from Native American Cultures – Facts, Regions & Tribes – HISTORY

Koch, A. et al. (2019) ‘European Colonization of the Americas Killed 10 Percent of World Population and Caused Global Warming’, The Conversation, retrieved from Colonization of Americas decimated population, caused global cooling (pri.org)

Krippner, S. and Thompson, A. (1996) A 10~Facet Model of Dreaming Applied to Dream Practices of Sixteen Native American Cultural Groups, Dreams 6(2): 71-96

Lakota Republic (2021) Seven Sacred Rights of the Lakota Oyate. Retrieved from Seven Sacred Rites of the Lakotah Oyate : Republic of Lakotah – Mitakuye Oyasin

Marshall, J. (2006) The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living. Blackstone Audio Books.

Morrison, D. (1992) Secret Society of the Shamans. Global Communications.

Nabokov, P. (1991) Native American Testimony – A Chronicle of India-White Relations from Prophecy to the Present, 1492-1992. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books.

National Park Service (2020) https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/sitting-bull.htm#:~:text=On%20several%20occasions%2C%20the%20visions%20given%20to%20Sitting,against%20travelers%20and%20forts%20along%20the%20Bozeman%20Trail.

Spence, L. (1988) The Encyclopaedia of the Occult. Bracken Books: London.

Tedlock, B. (2004) ‘The Poetics and Spirituality of Dreaming: A Native American Enactive Theory’, in Dreaming 14(2-3): 183-189.

Copyright © 2021 Daniel J Taylor

“have we lost sacred knowledge about the power of our dreams?”

I think so but we are starting to reconnect with our dreams or so I Hope.

This article reminded me of a conversation a while ago with a friend about the impact that colonialism had with the message “our dreams are more important than yours”, definitely a topic to consider…

And I like that there is the picture of a turtle as it is a common image of my dreams.

LikeLiked by 1 person